The

Hans Holbein Foundation resource centre for research and development

The

Hans Holbein Foundation resource centre for research and development

Vol.

V, No. 3., August 2004.

HOLBEIN, SIR THOMAS MORE

& THE PRINCES IN THE TOWER

The

disappearance of two boy princes from the Tower of London in 1483 remains the

greatest,

most baffling and longest running case of missing persons in the history of royal England. It is unsolved.

Read the

remarkable “Sir Thomas More and The Princes in the Tower”

--

encrypted messages for posterity by More’s friend Hans Holbein the Younger.

Holbein

claims he met both princes, now married with families, in More’s house in the

reign of Henry VIII.

Holbein

gives us their cover names. We know where they are buried. Holbein’s claim is

“testable” -- by DNA profiling.

The Author

Jack

Leslau was born in London in 1931. His discovery of the so-called Holbein Codes

surprised the academic world

since it

was unpaid work by a self-taught amateur.

What the UK Media say about Jack Leslau :

“How Holbein Hid a

Royal Secret”

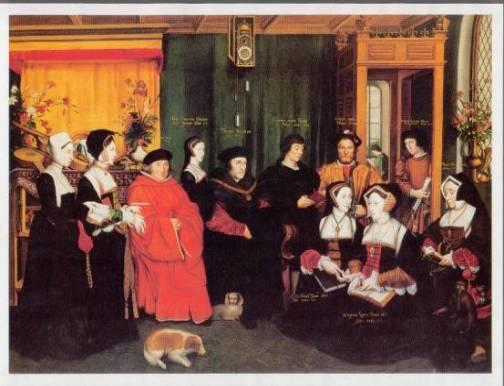

‘The

picture on the right may or may not have been painted by Holbein in Chelsea in

1540. According to Jack Leslau, this

portrait

of Sir Thomas More and his family contains clues proving that Richard III did

not murder the little princes in the Tower

–

and that no such murders took place at all.’ Report by Geraldine Norman,

SPECTRUM Article, The Times, 25 March 1983, p. 12

“Painting unveiled again.”

‘The Lord

Chancellor, Lord Hailsham, talks to Lord St. Oswald after yesterday’s unveiling

of the painting.’

Article

by Michael Hickling, The Yorkshire Post, 26 March 1983, p. 3

“Princes in the Tower lived on with secret identities.”

Article

by Annabel Ferriman, The Observer, 11 August 1991, p. 7

“Genetic

Hunt for Princes in the Tower.”

Article

by Peter Pallot, The Daily Telegraph, 13 August 1991, p.14

“DNA may solve Princes’ riddle.”

Article

by Lewis Smith, Sunday Express, 6 August 1995, p. 31

“Will DNA prove the princes lived?”

Article

by Annabel Ferriman, Independent on Sunday, 6 August 1995, p. 8

“The Princes in the Tower”

‘The

true fate of Edward and Richard, the two young princes who disappeared from the

Tower of London in 1483, is under

multi-disciplinary

review. “The greatest mystery in English history will be resolved by

scientists,” says Jack Leslau of the

Friends

of Thomas More. Scientists in the United Kingdom, Europe and the United States

will test Leslau’s theory that the

princes

were in fact not murdered and that the story was a successful Tudor deception.’

Article by Sir Gordon Wolstenholme,

former

Harveian Librarian, Royal College of Physicians, BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL,

Vol. 303, p. 382, 17 August 1991.

“BBC NEWS & CURRENT AFFAIRS : SPECIAL

CURRENT AFFAIRS PROGRAMMES, RADIO.”

‘Dear Jack Leslau, Thank you very much for coming to Broadcasting House to take part in our arts pilot programme.

I

thought your remarks during the discussion were fascinating and I shall watch

news of your bid for the DNA tests

with

great interest.’ Signed, Sheila Cook, Senior Producer, BBC News &

Current Affairs Programmes, 22 August 1991.

RICHARD III SOCIETY

Patron

H. R. H. The Duke of Gloucester

‘Dear

Jack, Many thanks indeed for your lecture on Tuesday last. Next time, maybe we

should start specially early so as

not

to run out of time! I hope you felt it was worth while: we certainly did, and

we had our all time maximum audience – 108.’

Signed

E. M. Nokes, General Secretary, dated 17 September 1992.

“Copy or Original?” The Family of Sir Thomas More

‘A number of tests carried out during its recent restoration, and extensive research carried out by Jack Leslau, have once again

reopened

the controversy as to its authorship, date and interpretation. The restored

canvas, measuring 12ft by 9ft, was unveiled

last

month by More’s successor in office Lord Hailsham, and is once again on view at

Nostell Priory, Wakefield, Yorkshire.

Article

by Susan of COUNTRY LIFE, p. 924, 14 April 1983.

“Pass Notes” No.

667: The Princes in the Tower

‘Ages?:

That depends.

On

what? On whether Richard III had the two princes done

in at the ages of 14 and nine.

Everyone

knows he did. You try telling that to Jack Leslau…’

The

Guardian, Weekend Front 2/3, August 1995.

Comment from abroad :

USA, Europe, Asia and Oceania

“University

of Arizona confirms Holbein painting is authentic.”

Article

by Carla McClain, Tucson Citizen, 2 March 1983, p.4

“The Hidden Rebus in Hans Holbein’s Portrait

of the Sir Thomas More Family.”

‘Although

the authenticity of the Nostell Priory portrait of the Thomas More family as a

Holbein original has become the subject

of

a raging controversy in art history circles, the discovery of the hidden rebus

in the painting may cause significant change

in

the recorded history of 16th-century Tudor England.’ Article by

Thomas Van Ness Merriam, EXETER,

Bulletin

of Phillips Exeter Academy, Exeter, N. H. 03833, USA. Summer 1983.

“How Holbein hid a royal secret.’

Sydney

Morning Herald, N. S. W., 18 June 1983, p. 42

“SECRETARIAT OF STATE -- FROM THE VATICAN”

‘Dear

Mr. Leslau, The Holy Father has directed me to acknowledge your letter and to

thank you for the copy of your lecture.

His

Holiness appreciates the sentiments which prompted this devoted gesture and he

invokes upon you and your colleagues

the

peace and joy of our Lord Jesus Christ. I also have the honour to convey his

Apostolic Blessing. Yours sincerely,’

Signed,

C. Sepe, Assessor, dated 28 February 1989.

“11 January 1990. Jack Leslau delivers a lecture, filmed for a TV documentary, on the Princes in the Tower,

at the Athenaeum Club, London.”

BULLETIN

THOMAS MORE, January 1990, p. 21 (Moreana, the

bi-lingual [French and English] review of Thomas More Studies,

serves

as bulletin to the International Association Amici Thomae Mori, at the

Catholic University of the West at Angers, France.

“Historian finds clues to 500-year-old whodunit.”

Article

by Lee Levitt, JEWISH CHRONICLE, London, 23 August 1991, p. 5

“Centuries on, they’re still arguing about Richard III.”

Article

by Randi Hutter Epstein, SAUDI GAZETTE, Riyadh, 26 August 1991, p.1

“The Craziest Story I Ever Heard.”

‘It

is a wonderful story and my hands itch to get those skeletons over here.’ The

speaker is Vice-Rector Herman Van Den Berghe

of

the Catholic University of Louvain (KUL) whose Centre of Human Genetics has

worked out a technique with which the history of England

can

be rewritten. ‘It started when Nobel Prize winner De Duve called me. Next was

the craziest story I ever heard but that was in fact

as

probable as the other version of the history of The Princes in the Tower.’ Article

by Peter Van Dooren, Science Editor, De Standaard,

4

September 1991, p. 12

§1 THE PRINCES IN THE TOWER

The mystery of the Princes in the Tower has an

uncomfortable feel about it.

But no longer. A witness left

testimony in a painting and no one saw it

because it was hidden and in

code. Not everyone knows that !

The witness is POSITIVELY identified, the codetext decoded and

interpreted.

If you want to know more...click on.

Introduction

More than five hundred

years after the disappearance of two English princes, thirteen-year-old Edward

V and his younger brother, Richard, Duke of York, people still dispute and

contradict what happened.

Since the

princes disappeared from the Tower of London in the reign of Richard III, one

side say Richard had them killed, relying on a confession made some nineteen

years later by a person promptly beheaded by order of Henry VII. The other side

says it was a false confession extracted under torture. ‘Why wasn't there a public

trial ?’

And so the

dispute was born.

And as the

turbulent history receded further back into the past, the likelihood of

discovering new evidence of the true fate of the princes became more and more

improbable. But the outcome of this royal tragedy, which saw the birth of the

Tudor dynasty in England, the story of its remarkable consequences and the

extraordinary way in which those consequences came to be interactive and

inextricably intertwined with our story, begins very simply.

It begins with

a painting.

The person who

broke the code tells the story…..

JACK LESLAU : ‘I would like

to introduce you to the persons depicted in this painting. But first, I want

you to see if there is anything strange about the picture itself. For instance,

the clock door above Thomas More’s head is open.

To the right, in front of an

unstrung table harp there is an extremely odd vase with each handle upside-down

in relation to its companion handle.

In the right foreground, two

sisters wear dresses with sleeves made from material of the other sister’s

bodice : red velvet and cloth-of-gold.

There are more than eighty

anomalies in this painting and you may conceivably decide to identify them,

work out what they mean and what the artist is trying to communicate. You will

have help.

For the present, I have to

draw attention that this painting has been in the possession of the More family

since it was painted by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/8-1543) during the artist's second

visit to England (1532-1543). Recent investigation revealed an anti-Catholic

slogan on the painting, which appeared in the mid-18th century and was later

over painted with a spurious date and signature, 'Rowlandas

Locky 1530' or '1532'. Since the

only Rowland Lockey in the literature is known from about 1593, the latest

examinations in the UK and USA give this beautiful painting to Holbein, the

radiocarbon date corroborating authentic documentation and traditional More

family history. The scientific reports are published for the first time today.

(See : BOOKSTALL).

Point

and click first :

■ Jack LESLAU “The Princes

in the Tower” Moreana XXV 98-99 (Dec.1988) 17-36

■ Jack LESLAU “The More Circle : the

Antwerp/Mechelen/Louvain Connexion”

(Amici

Thomae Mori International Symposium MAINZ 1995)

See

also: EUROPA: Wiege des Humanismus und der Reformation Publ. PETER LANG, 1997

p.167-172

Sir Thomas More and his Family is reproduced by kind permission of the owner, the Lord St Oswald and

Trustees, and is on view to the public at Nostell Priory, Nr. Wakefield, West

Yorkshire, England. Further details are available from the National Trust

Office in York. Photograph, by Sir Geoffrey Shackerley.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Contents of this Web site link

directly to the above published articles :

48.2MB in 510 Files:

§2

SIR THOMAS MORE AND HIS FAMILY

by

Hans Holbein the Younger

Part One

¶The “new” History Theory

Part Two

¶Cryptology

The

case for a Holbein attribution

The

artist’s communication security

Art

and Information theory

Art

and Academia

Art

and NIET

Notes & References

¶The

royal styling on the tomb of Lady of Jane Guildford,

Duchess

of Northumberland,

In

the Thomas More Chapel of Old Chelsea Church

‘Ye

Right Noble and Excellent Princess’ :

an

interpretation.

¶Photograph

of the memorial plaque on the Northumberland Monument.

The

rank and styling of:

Sir

Richard Guildford

Sir

Edward Guildford

The

‘High and Mighty’ styling of:

John

Dudley, Duke of Northumberland.

Why

is the Duchess of Northumberland buried in an obscure parish church ?

Why

isn’t the Duchess buried in one of the Dudley family vaults ?

The

contemporary witness Holbein provides compelling new evidence to explain the

mystery.

The

roles played by Chroniclers :

Edward

Hall

Raphael

Holinshed

“Royal

Cousins”

Anecdotal

history of a great grandson of Edward IV,

Sir

Philip Sidney --

(“a

rightful heir”)

And

a great granddaughter of Edward IV,

Elizabeth

I --

(“a

legal heir”)

James

IV of Scotland: the King James Version of the Bible.

The

on going inquiry: Elizabethan, Jacobean & Stuart.

Acknowledgements

Addenda

& Corrigenda

¶Benedictus

Smythe : The illegitimate son of John Clement.

¶The

on going method of inquiry

Negative

Intelligence Evaluation Theory (NIET)

¶Investigation

in Flanders

Report

¶Investigation

in England

Report

¶The

Saint

¶Reactions

to John Guy’s BBC documentary

¶Monarchy

Henry

VIII : ‘A sexual impediment of some consequence’ : an article

Read

:

1.

Holbein’s cryptic comment on the prime cause of the re-marriages of the king

2.

The published opinions of Royal Physicians on Henry VIII’s medical case history

3.

The NIET investigation of the genetic case history

The

amazing and definitive conclusion

…………………………………………….

Readers’

Comments

¶National

Security Agencies

Agency

Comments

¶Writers

and Publishers

¶B.

Fields ; G. Tournoi ; A.J. Pollard ; A. Weir ; D. Wilson ; D. Baldwin.

“

Gentlemen versus Players”

The

amateur takes on the professionals in a one-wicket match.

The

professionals have batted (five centuries) and now it’s the turn of the

amateur.

He

is using the latest bat made by science : A “Nike DNA Profile”.

The

fielding side do not have modern technology.

They

move in ever decreasing circles.

The

batter bats steadily on.

“Read and

Reap”

.

”The

Female of the Species”

(A

translation of history into drama for the stage)

‘If

you are sensitive to this sort of thing, Jack Leslau’s “Female of the Species” (2003)

outstrips in horror Akiro Kurosawa’s “Ran” (1985)’

The

number is 5.

¶John

Clement MD : Scholar/Warrior.

¶Thomas

Clement MA, son of John Clement, Godson of Thomas More.

¶Caesar

Clement DD : the illegitimate son of Thomas Clement

¶The

Will of Caesar Clement

(‘Wills

and daily books of record are meat and drink to a researcher!’)

¶’Talking

Pictures’

#4.

“Mona Lisa” by Leonardo da Vinci.

Parts

I & II

1503

: Leonardo tells us his model is Magdalena Offenburg in the world’s most famous

painting.

1526

: Holbein confirms this identification in the same secret method of

communication invented by Leonardo.

Both

men paint a famous hetæra.

Magdalena

Offenburg, now in a position of distinction, is scandalized.

Holbein

is more interested in his tribute to Leonardo.

There

is more. For instance, the unknown provenance of the Holbein and Leonardo items

in the Royal Collection.

For

the first time we have a complete theory.

It

is new. It is astounding !

#3.

The Ambassadors by Hans Holbein the Younger.

1.

The restoration of The Ambassadors at the National Gallery, London : a

scientific analysis.

2.

North J.D. The Ambassadors’ Secret ; a critical review.

3.

The artist’s secret method of communication : the cryptosystem.

4.

Interpretation of the personal and political information : the decrypts.

‘Jack

Leslau points to a major anomaly post-restoration by the National Gallery’.

#2

Henry Pattison : “The Henry VIII ‘look-alike’”

Holbein

claims this former servant of Thomas More lost the Lord Mayor ‘s sword!

(The

Sword Bearer still carries the giant ceremonial sword in procession on Lord

Mayor’s Day)

#1.

Sir Henry and Lady Mary Guildford : “New” evidence from the Court of

Henry VIII

‘Up close personal and political’.

#0

“Figs and Figments”.

The

fig leafs in the Holbein paintings : an interpretation.

¶The

LESLAU Conjecture

Richard

III

Sir

James Tyrrell

Perkin

Warbeck

¶General

History

Sovereigns

since the Norman Conquest

Genealogical

Charts I to VIII

Lancaster

& York

Beaufort

Tudor

Neville

Woodville

Bourchier

Dukes

of Buckingham

¶Calendar

of Events

(1470-1572)

THE JACK LESLAU NEWSLETTER & NOTICEBOARD

An

introduction to Tudor history

The

play : The Debt.

What’s the difference between an overt and a covert rebus?

From direct inspection,

this drawing above is obviously a puzzle and you are invited, in an open way,

“Solve the puzzle !” This is an overt rebus and I am today inviting YOU

to solve it. You will have help at jack.leslau@skynet.be.

On the other hand, the covert

rebus is not at all obvious. Encryption adds the element of secrecy to the word

transformations. OK ? Decryption strips away the secrecy leaving the linguistic

equivalents, which make sense (they MUST make sense!), relevant to known

history.

Please don’t worry if you do not immediately grasp

the significance of the remarkable covert rebus. You are in good company. It

took nearly five hundred years to work out that Holbein was risking his life to

communicate personal and political history for posterity, for US, and

how brave and clever he was.

§6

BOOKSTALL

Thomas MERRIAM

Moreana XX, 79-80 (Nov. 1983), 111-16

UNVEILING

OF THE MORE FAMILY PORTRAIT

AT NOSTELL

PRIORY

On

the afternoon of Friday, 25th March 1983 (Lady Day), the Right

Honourable, the Lord Hailsham of St. Marylebone, Lord Chancellor of England,

unveiled the newly restored 8 x 12 foot (2,5 x 3,5 meters) Group Portrait of

Sir Thomas More and His Family at Nostell Priory, Wakefield, West

Yorkshire before a distinguished audience. It was a glittering occasion with

flashbulbs and television lights, contrasting in their brilliance with the

sombre stone hall. Lord Hailsham chose his words with care and precision worthy

of the senior law officer. He spoke of his admiration of the painting and his

belief it was by Holbein. He suggested a parallel between the situation of More

and Boethius, whose << De Consolatione Philosophiae >>

features in the painting.

The

family portrait 1 is one of several

versions that appear to be based upon a Holbein sketch in Basel (No. 402). A

modified copy by Rowland Locky hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in

London. This painting measures approximately 7 x 11 feet and is curious in its

including four descendants of More, who were alive in 1593, with seven of the

Thomas More family, as portrayed from life in the 1520s (No. 404). A much

smaller Locky version in the Victoria and Albert Museum contains further minor

variations (No. 405).

Sir

Roy Strong states, in his Tudor and Jacobean Portraits in the National Portrait

Gallery, that the Nostell Priory painting is a copy by the same Elizabethan

miniature painter, Locky 2. The evidence he

adduces for the attribution is the signature in the lower right-hand corner of

the canvas. The name – Richardus, Rogerus, or Rolandus /Rowlandas Locky – bears

with it the date 1530 or 1532. Sir Roy has rejected the apparent date (Locky

was probably born in the 1540s) and has assumed it to be variously 1592 or

1593. 3 The Holbein original painting, from

which it is presumed to have been copied, is believed to have been destroyed by

fire in 1752 at Kremsier, Germany (No. 401).

The

Winn family have been in possession of the Nostell portrait since the marriage

of Sir Rowland Winn to a Roper heiress in the eighteenth century. At that time

it was taken from Well Hall, Eltham, to Yorkshire. The family tradition has

held the painting to be a Holbein painted for Margaret Roper and her husband

William. Both John Lewis and George Vertue described it as a Holbein in their

time. In 1717 Lewis remarked on items in the painting only three inches from

where the Locky signature appears today, without mentioning the Locky

attribution.

Is

it possible that the signature was added after 1717 ?

The

present owner, Lord St. Oswald, had received some highly interesting

information before the unveiling. On 7th January 1982, Dr. Paul

Damon of the Laboratory of Isotope Geochemistry at the University of Arizona

received for radiocarbon dating a strip of the original canvas, cut from the

lower sight edge of the painting during restoration. After he had washed the

linen free of paint and animal glue, the original eight grams shrank to four

grams of pure linen cord. These four grams were insufficient to create the

required volume of carbon dioxide gas for the 2.5 liter counters operated at

three atmospheres. Dr. Damon had to dilute the specimen gas with pure inert CO2,

containing no carbon 14. Additional delays were caused by

contamination of the sample with radon gas ; a month was required for storing

the gas to allow the radon to decay to insignificance.

Finally, on February

14, 1983, he produced his report with its startling conclusion the << the

calendar age of the harvesting of the flax lies between A.D. 1400 and A. D.

1520 >>. Thus it was << compatible with the painting being an

authentic Holbein the Younger >>. It was, in other words, unlikely that

Rowland Locky had chosen a seventy-year-old canvas to execute a difficult major

work in or about 1593.

Armed with this new

piece of knowledge, Lord St. Oswald informed the press. The first announcement

in the national press was a short article by Donald Wintersgill in << The

Guardian >> of March 2, 1983, headed << Painting of More could be a

Holbein >>. Sir Roy Strong, Director of the Victoria and Albert Museum,

was quoted as doubting the conclusion of Dr. Damon : << How developed as

a science is the carbon dating of the canvas ? >> he asked. << In

my opinion, in no way is this a Holbein. It is a very complicated subject. The

original was confiscated when More fell from power. >>

One edition of

<< The Guardian >> for the same day contained a further quotation

from Sir Roy : << If canvas can be carbon dated, it would be of great

significance. I would like to see it done on authentic paintings of which the

dates are known. >>

When I queried this

quotation, he wrote me that it was not quite true that he stated that it was

doubtful that canvas of the sixteenth century could be carbon dated. The

important point, he emphasised, was that the canvas was signed and dated

Rowland Locky, 1592. 4

Not only was this

prominent art historian opposed to the Arizona findings ; E. T. Hall, of the

Oxford Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, reported to

Geraldine Norman of << The Times >> (25 March 1983) that the odd

<< hump >> in the radio carbon calibration chart for the sixteenth

century made it impossible to distinguish the early years from the late ones.

Dr. Damon’s dilution of carbon dioxide in order to << stretch >>

it, moreover, made the results liable to error of 150 years. Professor Hall

wrote to me that he believed the dates 1580 and 1620 were as likely as the date

1520 cited by Paul Damon. 5

Dr. V. R. Switsur, of the Sub-Department of Quaternary Research at the University of Cambridge, was more favourable to Dr. Damon’s report. He estimated the dates 1407 and 1495 as the limits for the 95 per cent level of confidence, using the data from Arizona. Should the level of confidence be increased to 99 per cent, there was a slight possibility of a confusion between 1525 and the 1600-1620 period. 6

Writing in May to Mr.

Jack Leslau, Dr. Damon referred to the successful completion of a <<

blind inter laboratory test >> which gave confirmation to his findings on

the dating of the canvas of the Nostell portrait. Dr. Switsur was Dr. Damon’s

choice as an expert on radiocarbon calibration in the United Kingdom.

Although the

scientific controversy has still to be resolved, Lord St. Oswald was

sufficiently satisfied by the reports from Dr. Damon and Dr. Switsur to invite

the present Lord Chancellor to officiate at the elegant ceremony at Nostell.

After its restoration in a Chelsea stable, formerly part of More’s estate, the

newly framed painting was resplendent.

But what of the

signature on the painting and the disputed date, 1530/1532 ?

An

infra-red photograph, taken in 1951 at the National Portrait Gallery, revealed

interference and a partially disfigured date, possibly 1752. An examination by

microscope in January 1987 by the Courtauld Institute indicated that an

original eighteenth century date had apparently been changed by additions of

brown/grey and blue/black semi-transparent << overpaint >> to

create the 1530 or 1532 now visible. 7

Further examination by the Hamilton Kerr Institute of Cambridge indicated that

the Locky signature was a later addition and spurious. A pig’s snout had been

clearly superimposed on the nose of the little dog, directly in front of St.

Thomas More, probably at the same time as the other alterations.

On

the day of the unveiling, << The Times >> published a long article

by Geraldine Norman, entitled << How Holbein hid a royal secret >>.

It described the discovery by Jack Leslau in 1976 of a concealed rebus in the

Nostell painting, similar to others in the work of Hans Holbein the Younger.

Seen from a special point of view, the single glove held by Elizabeth Dauncey

may read << le pair lui manque >> for << le père

lui manque >>, and covertly refers to the illegitimacy of her visible

pregnancy.

The

purple peony on the left of the canvas is an unconventional symbol ; it

secretly << marks >> one of the persons with the symbol of <<

royalty >> and << medicine >>. (<< Peony >> was a

nickname for a doctor, as Paion was physician to the gods in Greek mythology).

Another

flower is a << Richard-Lion-Heart >> and << marks >> an

alleged Plantagenet in the painting. The carpet on the sideboard signals a

cover-up -- << faire la tapisserie à la crédence >> or

<< cacher la crédence sous le tapis >>.

The

cover-up referred to is the concealed existence of the younger son of Edward

IV, Richard, Duke of York, as Dr. John Clement. His alleged murder by Richard

III, described by More thirty years after his disappearance, was a <<

blind >> to protect him. << Est-ce (esses) gauche ou réflexion

faite, est-ce (esses) à droite? >> ask the reversed S’s on the chain

(of the Duchy of Lancaster) that hangs from More’s neck. Clement stands,

depicted at half his age, in the doorway ; he is dressed in the Italian style,

having studied medicine at Siena and probably at Padua.

<<

The Times >> later published four letters referring to Geraldine Norman’s

article. Mark Bostridge (April 4, 1983) argued that the Nostell painting was a

Locky copy of the lost Holbein original, given to William Roper, son of William

and Margaret Roper. Holbein would not have dared paint a huge canvas for the

Ropers while serving as court painter to Henry VIII after the martyr’s

execution. Furthermore, the date 1530 was incompatible with Holbein’s sojourn

in London. The cramped perspective was inconsistent with Holbein’s practice. If

John Clement was in fact Richard Plantagenet, he would have died at the

unlikely age of ninety-nine in 1571.

One point should be

made in passing : the painting was not given to a son of William Roper of the

same name. No such person existed and the error is traceable to a publication

of the National Portrait Gallery ; Angela Lewi’s The Thomas More

Family (1974), p. 7. 8

A second letter,

from Lady Jacynth Fitzalan-Howard (April 6, 1983), accused Mr. Leslau of an

exuberant imagination. The single glove was merely a mark of rank in Tudor

Portraits. The customary place for carpets in the period was on tables and the

tops of cupboards. The purple peony was a mistake by the artist, like the

five-petalled Madonna lilies in the Locky version at the National Portrait

Gallery.

A third letter

found fault with Mr. Leslau’s French. P. J. Barlow (April 9, 1983) claimed that

joncachet was not French for a rush-strewn floor. Faire tapisserie

means << to be a wallflower >>. Crédence did not mean

<< belief >>, and a Turkish carpet was a tapis, not a tapisserie.

Finally,

a fourth letter by Eric Lyall (April 15, 1983) took issue with Mr. Barlow’s

criticisms. Mr. Lyall claimed jonchée was near enough to Jean caché

to serve as a sixteenth century rebus pun for a hidden John Clement. Tapisserie

could also mean a carpet and crédence was << belief >>. He

concluded with an opinion based on a different interpretation of one of Mr.

Leslau’s rebuses. Porter à faux means << to be inconclusive

>>.

Thus

ended the correspondence to << The Times >>. Jack Leslau’s

rebuttals to the three critical letters were not printed. 9 Although many letters were received by <<

The Times >> in connection with the Geraldine Norman article, popular

interest had by this time, no doubt, shifted to the feigned Hitler Diaries. Had

it not been for Jack Leslau’s absorbing interest and energy in the face of

numerous rebuffs, however, the Nostell portrait would never have been closely

examined by the Courtauld and the Hamilton Kerr Institutes. The carbon dating

would not have taken place. Without the carbon dating, is it likely that Lord

Hailsham would have lent his dignity to the unveiling of a work commonly held

to be a copy ? Jack Leslau’s hours of work deserve more than an unconsidered

dismissal by art historians and scholars, and, above all, lovers of St. Thomas

More.

Basingstoke, Thomas MERRIAM.

NOTES

1. See The Likeness of Thomas More by Stanley Morison

and Nicolas Barker, London, 1963, chapters 6 & 7, for a discussion. The

Nostell portrait is catalogued by Morison as No. 403. Figures in parenthesis

refer to this book.

2. Roy Strong, Tudor and Jacobean Portraits in the

National Portrait Gallery, London 1969. Vol. I, p. 349.

3. Ibid, p. 349 << Locky executed three

versions in all : (i) an exact copy of the Holbein as it then was. This is now

at Nostell Priory and, although it bears the impossible date 1530 it would seem

reasonable to conclude that it was painted at the same time as no. ii in

1593…>> The reference no. i is to Morison’s No. 403 ; no. ii is to

Morison’s No. 404. In a letter to the author, Sir Roy Strong stated the Nostell

portrait was dated 1592. See our next note.

4. The undated letter was received from Sir Roy Strong

in May 1983 in answer to the author’s request for a clarification of his

newspaper statement published in << The Guardian >>. The author

stated that he was preparing an article for a journal. Sir Roy said in the

letter, <<…The important point is that regardless of the date of the

canvas, the picture is signed and dated by an Elizabethan artist, Rowland

Locky, 1592. In respect of canvas dating, I feel that this is an area of

research that may prove to be highly interesting but at the moment could hardly

be regarded as in any way being beyond an exploratory stage. >> (End of

letter) The author further queried Sir Roy Strong’s date in the light of

evidence that the signature and date are spurious. Sir Roy has yet to reply.

5. Letter from Professor E. T. Hall, dated May 20

1983, with specific permission to quote from it. Calibration charts included.

6. This information is contained in a detailed

letter to Lord St. Oswald, dated March 21 1983, calibration charts included.

7. << An infrared photograph of the

inscription on the Group Portrait at Nostell, taken at the National Portrait

Gallery, London, in 1951, revealed an hidden and partially disfigured date,

possibly ‘1752’, which has been inexplicably overlooked in the past. A

preliminary and inconclusive microscopic examination of the portrait in January

1978 by Robert Bruce-Gardner, Acting Director of the Technology Department, The

Courtauld Institute, revealed (in part) three separate applications of paint

and the relevant missing outline of the date (identified by me) which I deduce

was probably due to the interference reported in writing by the National

Gallery in 1951. The recommendation was made that the date and inscription

should be examined further, the possibility of my date-identification not

excluded ; and although Bruce-Gardner was willing to do this the portrait was

too large to permit entry to the workrooms of the Courtauld Institute. >>

Jack Leslau wrote this in The Ricardian, Vol. V, No. 64, (March 1978),

p. 24.

8. Kai Kin Yung, Registrar of the National Portrait

Gallery, confirmed in a letter to the author, April 26 1983, that this was an

error.

9. They are dated April 7, 9 and 14, 1983.

HOLBEIN’S

COVERT REBUS

In the summer 1983

issue of Exeter, the bulletin of Phillips Exeter Academy, New Hampshire,

Summer 1983, the leading article, by Thomas V. N. Merriam (class of 1950), is

entitled << The Hidden Rebus in Hans Holbein’s Portrait of the Sir Thomas

More Family. >> The illustrations, essential for the thesis, include the

portrait of Richard III (p. 12), since Jack Leslau finds a resemblance between

him and the young man standing in the doorway of the Nostell painting, and uses

this << air de famille >> as further evidence for

identifying the young man as Richard of York. The Basel sketch of the More

family group (p. 13) and the Nostell canvas (pp. 58-59) are reproduced, so we

are challenged to detect some of the eighty-odd differences in lay-out and

detail which J. Leslau interprets as symbols giving cumulative support to his

<< revisionist history of the Tudor period >>. A few photographs

show Jack Leslau with the author, and with Lord Hailsham and Lord St. Oswald.

Much is made of negative evidence : thus the total absence of any portrait or

any holograph record (were it only a signature) of Dr. John Clement while he

was President of the College of Physicians is exploited to confirm that he was

a << notional person >>, merely destined to cover the identity of

Prince Richard, << rightful heir >> to England’s throne from 1528,

after the death of Edward V (covered by another notional person, Sir Edward

Guildford). Other elements – carbon dating against Locky’s claims, etc. – are

touched in much the same was as in Mr. Merriam’s article (supra,

pp. 111-16). We reproduce the Basel drawing to invite comparison with the

Nostell painting.

G.M.

Last Reviewed : 14 June 2000

ã2000

Holbein Foundation. All rights reserved. Terms of Use.

Click ç “Back”

Thomas

MERRIAM Moreana XXV, 97

(March 1988), 145-152

his identity and his Marshfoot House in Essex.

Students of More need no introduction to John Clement, the << puer

meus >> of Utopia. His origins and date of birth are

unknown. He is said to have attended St. Paul’s School in London, studying

under the classicist William Lily. There appears to be no independent

corroboration from school records. By the year 1514 he is reported to have been

a member of More’s household, where he was tutor to More’s children in Latin

and Greek. Unless this be part of More’s affabulation, he took << the boy

Clement >> along to Bruges and Antwerp on his 1515 embassy. In More’s

house Clement met his future wife, More’s << adopted >> daughter,

Margaret Giggs, whose age in 1527, according to the sketch of the More family

portrait in Basel, was 22, exactly the same as her cognata Margaret More

Roper.

In 1518 or 1519 Clement is reported to have been appointed Cardinal

Wolsey’s reader in rhetoric (Latin) at Corpus Christi College, a college

founded by Bishop Richard Foxe of Winchester and dedicated to the new

humanistic curriculum. 1 Somewhat later,

Clement was made reader in Greek at Oxford 2

and he lectured to a larger audience than anyone before. 3 Nonetheless he left Oxford in the 1520s in order

to study medicine in Italy. He appears to have travelled via Louvain and Basel,

where he met Erasmus. 4 He brought a copy

of Utopia to Leonico at Padua in 1524. 5 By

March 1525, he received his M. D. at Siena ; his combined skills in classics

and medicine enabled him to help Lupset, his successor at Oxford, complete the

Aldine edition of Galen at about the same time. 6

In 1525 Clement was

a member of the royal household as Sewer [Server] of the Chamber ultra mare.

7 His name, listed as from London, is included

among the other sewers of the chamber in the accounts for 1526. 8 On his return to England, Dr. Clement was

admitted to the College of Physicians in London on 1 February 1527-8. He was in

the king’s service when sent with two other royal doctors under Dr. Butts in

1529 to attend Cardinal Wolsey, now out of favour and languishing at Esher. 9 In 1535, he was consulted on the liver of John

Fisher, then a prisoner in the Tower. 10

Three years later, the records show him receiving from the royal household a

salary of £10 semi-annually. 11 In 1539,

however, the salary was cancelled. 12 Clement

was made president of the College of Physicians in 1544. Jack Leslau has found

that the College possesses no documents signed by him as president. This has

been confirmed the Wellcome Foundation. 13

The biographical article

in the DNB fails to mention a number of curiosities regarding John

Clement. It is customarily assumed that he was born around 1500 making him a

boy when he first joined the More Household, and hence the puer meus of Utopia

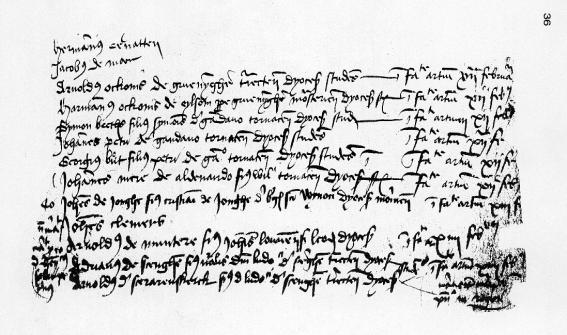

(1516). 14 There is, nonetheless, an

entry in the register of the University of Louvain of the enrolment of a

<< Johannes Clemens >> on 13 February 1489, with the note

<< non juravit >> added. 15 The

name John Clement is not common on the Continent except as a combined Christian

name. The note << non juravit >> is unusual in the Louvain

register, and it is remarkable to find the undoubted John Clement of our

account appearing in an entry of January 1551 with the unique note :

Joannes Clemens, medicine doctor,

anglus, nobilis (non juravit ex rationabili quadam et occulta sed tamen

promisit se servaturum consueta). 16

The chances of

there having been two non-juring John Clements without family background or

specific place of origin within sixty-two years of each other are negligible.

It is interesting

to read also of Clement’s imprisonment in the Fleet following More’s own

imprisonment in the Tower. A letter written by John Dudley to Thomas Cromwell

on 11 October 1534 states :

<< farthermore as towchyng maistr

Clements mattr I beseche your maistership not to gyue to much credens to some

great men who peraventure wyll be intercessours of the matter and to make the

beste of it for Mr Clement / by cause peraventure they theym selves be the

greatest berers of it / as by that tyme I have shewed you how whotly the

sendyng of Mr Clement to the flete was taken, by some that may chawnce you

thynke to be your frende / you wyll not a little marvayle / … >> 17

One authority

states that Clement was imprisoned in the Tower with More refusing to take the

Oath of Supremacy. 18

In 1545 John

Clement and his wife were granted the lease of Friar’s Mede, Marshfoot in

Hornchurch, Essex, for thirty years at 20 shillings per annum by New College,

Oxford. 19 In 1549, Friar’s Mede was

leased, as it were, from under Clement : the new regime under Edward had begun.

Clement left the country for Louvain. He lost his extensive library at his town

house in Bucklersbury, consisting of 180 books, and was unable to regain them

on his return to England in the reign of Mary. 20

The site of Marshfoot

is discernible today at Ordinance Survey grid reference TQ 513 825. It lies not

far from the electric railway linking Rainham with Dagenham. Slightly sunken

from the lane, the plot can be made out on the edge of the former marsh land

which stretches south towards an invisible River Thames.

The Public Record

Office in Chancery Lane contains an inventory of Marshfoot house listing the

items which were confiscated by Sir Anthony Wingfield with the approval of no less

a personage than Sir William Cecil, the future Lord Burghley. The inventory is

dated 28 August 1552, twelve days after the death of Wingfield. 21 The complete listing is too tedious to

transcribe. In the chamber over the hall there were << cusshins with

dragons pictures >> and << an olde turkey carpet >> among

other items including << a shefe of arrows >>, << ij paire of

splents ij salletes / an armyngswerd(e?) a poole axe / iii bills >>.

Whether such weaponry was common among physicians of the time, I am unable to

say.

There

was a chapel chamber in Marshfoot and it contained the following items, which

were notably Catholic : << an awlter / a picture of our Lady / a picture

of the v wowndes / a masse booke / ij cruetes >>, << a surples

>>, << iij latten candlesticks for tapers >>, << a

hallow water potte >>, << a portesse with claspes of silver and

gilte / >>.

The

picture of the Five Wounds calls to mind the banner insignia of the Pilgrimage

of Grace, the most serious of all the rebellions under Henry VIII. But the

picture may have been common in such a liturgical context. There is a touch of

poetry in the << dove house with a smalle flight of doves / with a hansom

garden place but overgrowne with grasse / >>. It is a description of a

place waiting for the overdue return of its owner. Clement was unable to regain

his lost possessions after he returned to England on 19 March 1554.

Nonetheless, his former importance was restored under Mary. In 1554 his son,

Thomas Clement, M.A., was granted a royal annuity of £20. 22 With Mary’s death and the accession of

Elizabeth in 1558, the Clements took leave of England for the last time. Four

years later (March 1562) John Clement appears in the Louvain register :

<< Dominus Joannes Clemens, nobilis, Anglus. >> 23 The similarity with the previous entry in

January 1551 is unmistakable. What is the meaning of nobilis ?

Why Dominus ? Nothing in the known history of the More family suggests

that the Greek and Latin tutor was of noble birth.

The

last Louvain entry, dated 1568, is brief : << Dominus Joannes Clement,

in theologia >>. 24 The possible

span of the Louvain register entries is an astonishing 79 years ; it merits

further examination.

Shortly

before his death Clement moved from Bruges to Malines. He took up residence at

1 Blokstraat, a few feet from the church of Saints Peter and Paul, where lie

the remains of Margaret of Austria, 25 aunt of

Charles V and patroness of Erasmus, More, 26

and Josquin Des Prés. Margaret Clement died on 6 July 1570, the anniversary of

More’s execution, and was buried in St. Rombout’s cathedral in the Grote Markt.

Clement himself died on 1 July 1572 in the year that the Spanish sacked the

ancient imperial town, and was buried beside his wife near the high altar of

the cathedral. 27

Thomas

Merriam

35

Richmond Road

Basingstoke,

Hants RG21 2NX

*The

author would like to acknowledge the kind assistance of the following : Dr.

Marjorie McIntosh, Mrs. Anne Hawker, Mr. Jack Leslau, New College Oxford,

Corpus Christi College, Essex County Records Office, the Rijksarchief Antwerp,

the Royal College of Physicians, the Wellcome Foundation, the Institute of

Historical Research of the University of London, and the Public Record Office.

NOTES & REFERENCES

1. The

Dictionary of National Biography, IV, 489. Mention should be made of the

one published biography, John Clement by E. A. Wenkebach (Leipzig,

1925).

2. DNB,

IV, 489. Sir Kenneth Dover, President of Corpus Christi College, Oxford wrote

to the author, 22 February 1984, as follows : << So far as I can discover

(from Fowler’s very detailed History of C.C.C.) (pp. 88, 369) the sole

evidence for Clement as lector is Harpsfield. Hist. Eccl. Angl.

p. 644. Clement was lector in Greek (not rhetoric & humanity) from 1518(?)

to 1520, & there is no record of his ever having been a student at the

College. The fact that his appointment was in Greek makes all the difference, I

think : there weren’t many people around who could teach Greek. >>

3.

Maria Dowling, Humanism in the Age of Henry VIII (London, 1986), p. 31.

4. A. B. Emden, A Bibliographical Register of the

University of Oxford A.D. 1501-1540 (Oxford, 1974), p. 121.

5. F.

A. Gasquet, Cardinal Pole and His Early English Friends (London, 1927),

pp. 69-71.

6. Emden, p. 121.

7. A.

W. Reed, << John Clement and His Books >>. The Library,

4th Series, vi (1926), p. 330

8. Letters

& Papers of Henry VIII (17 Henry VIII, 1526), IV, Part I, No. 1939(8).

9. DNB, IV, 489.

10. L

& P Henry VIII (27 Henry VIII, 1535), VIII, No. 856 (45).

11. L & P Henry VIII (30 Henry VIII,

1538), XIII, Part 2, No. 1280 (f. 11b). This was the same amount as he received

from the same source in 1529 ; see L & P Henry VIII (20-23 Henry

VIII), V, 310.

12. L & P Henry VIII (31 Henry

VIII, 1539), XIV, Part 2, No. 781 (f. 68).

13. Most of the information on John Clement contained

in this article was uncovered by Jack Leslau and is taken from his research

article << Holbein and the Discreet Rebus >>.

14. The Complete Works of St. Thomas More,

Vol. IV: << Utopia >> ed. Edward Surtz, S. J., and J. H. Hexter

(New Haven, 1965), p. 40

15. A. Schillings, Matricule de l’Université de

Louvain, III, Août 1485 – 31 Août 1527 (Brussels, 1958), Entry No. 128, p.

42. Jack Leslau has pointed out that this entry stands out among the adjoining

entries it its absence of family, place of origin, or qualifying status.

16. A. Schillings, Matricule IV, Février

1528- Février 1569 (Brussels, 1961), entry no. 86, p. 423. During the

period covered by volume IV, out of some 26,000 students inscribed, the

classification << non juravit >> was applied in eight other

cases, five of them due to absence of the student at time of registration.

17. L

& P Henry VIII (26 Henry VIII, 1534), VII, No. 1251, PRO SP

1/86. p. 75.

18. Sir Michael McDonnell, The Register of St.

Paul’s School 1509-1748 (privately printed for the Governors, 1977).

19. Marjorie McIntosh, << References to

people surnamed Clement in the Havering/Hornchurch/Romford materials used by

Marjorie McIntosh >> (Unpublished research report).

20. A. W. Reed, pp. 329-39. His library contained 40

books in Greek, 139 in Latin, and one in English. Reed estimates their monetary

value at £30 13s 4d, or about US $50,000 today according to my estimate.

21. PRO SP10/14/71

22. Calendar of Patent Rolls (1 Mary, 1554) I, 309, dated 8 May 1554.

23. A.

Schillings, Matricule IV, entry no. 3, p. 634.

24. A.

Schillings, Matricule IV, entry no. 55, p. 738.

25. For the place of residence, DNB.

Notice the proximity of 1 Blokstraat to the church. I was informed by the

Mechelen tourist office that part of the body of Margaret of Austria is buried

behind the altar of the church.

26.

See Elizabeth F. Rogers, << Margaret of Austria’s Gifts to Tunstal,

More and Hacket (1529) >> in Moreana 12 (Nov. 1966), pp.

57-60.

27.

Jack Leslau, art cit. Part II, p. 5. Also DNB, IV, p. 489. See The

Correspondence of Sir Thomas More, ed. Elizabeth Frances Rogers (Princeton,

1947), p. 79. Also De illustribus Angliae Scriptoribus, item 768 --

<< In exilio Confessor obijt Mecliniae primo die Julij, anno post

aduentum Messiae 1572, & sepultus est in Ecclesia S. Romboldi prope

tabernaculum, iacentque in eodem tumulo coniuges…>>

POSTSCRIPT

The

following additional document concerns the age and status of John Clement. To

my knowledge, it is unique among written materials in tending to confirm the

evidence otherwise available solely from continental sources ; first, for

Clement belonging to an earlier generation than indicated by the presumed birth

date of 1500, and, second, for being of noble birth.

There

is a listing in Letters & Papers Henry VIII (2 Henry VIII), I, Part

2, Appendix, p. 1550 (f. 10d) of the challengers and those answering the

challenge at a feat of arms << pas d’armes >> planned

for the afternoon of Wednesday, 1 June 1510. The list is as follows :

King – Lord Howard King

– John Clement

Knyvet – Earl of Essex Knevet

– Wm Courtenay

Howard – Sir John Awdeley Howard

– Arthur Plantagenet

Brandon

– Ralph Eggerton Brandon – Chr. Garneys

It would appear that

each challenger took on two opponents during the afternoon. Of the ten participants

besides Henry VIII himself, Lord Howard, Thomas Knyvet or Knevet, the Earl of

Essex, William Courtenay, and Arthur Plantagenet were closely related by blood

or marriage to the king.

Two participants,

Lord Howard and Charles Brandon, were to become the premier peers of the realm

as the Dukes of Norfolk and Suffolk.

Those related to the

king belonged all to the generation of the king’s mother, Elizabeth of York.

Who were the five relatives ?

Lord Thomas Howard

was to become better known as the third Duke of Norfolk when his father, the

second Duke, died in 1524. Born in 1473, he was 37 or thereabouts in June 1510.

The king was less than 20. Thomas Howard II was then married to Anne

Plantagenet, sister of King Henry’s mother. He was the king’s uncle by

marriage.

Sir Thomas Knyvet or

Knevet was the son of Eleanor Tyrrell, sister of Sir James Tyrrell, reputed

murderer of the Princes in the Tower. He was married to the sister of Lord

Thomas Howard. His brother Edmund seems to have studied under Colet, being

named in Colet’s Will.

Henry Bourchier,

second Earl of Essex, was Henry’s cousin, the son of his great aunt, Anne

Woodville, sister of Elizabeth Woodville. He too belonged to the older

generation, possibly born in 1471. If this is true, he would have been about 39

in 1510.

William

Courtenay, 18th Earl of Devonshire, was married to Henry’s aunt

Catherine, sister of Elizabeth of York.

Arthur

Plantagenet was the illegitimate son of Edward IV by his mistress Dame

Elizabeth Lucy. He was therefore half-brother to the king’s mother and to the

wives of Lord Howard and William Courtenay.

Howard, Bourchier,

Courtenay and Plantagenet were of the blood royal in their own right,

irrespective of other links in the case of ties by marriage.

Charles Brandon, future

Duke of Suffolk, would become Henry’s brother-in-law after his marriage to the

king’s sister Mary on the death of her husband, the French king. He was younger

than the others, having been born in 1484.

If we look at the

ages of the noble guests on the afternoon of 1 June 1510, we find that the

conventional John Clement, puer meus of ten years of age, would be

notably out of place. However, a John Clement who had been in his teens at

Louvain in 1489 would be a contemporary. Furthermore, a noble John Clement

would be an appropriate answerer to the king’s challenge in the company of such

distinguished companions.

Résumé

en français.

Pour

le Dictionary of National Biography, John Clement est un homme de naissance modeste

qui à 15 ans accompagne More à Bruges en 1515, étudie puis enseigne à Oxford,

devient docteur en medecine a Padoue, épouse une fille adoptive de More,

preside le Collège des Médecins, s’exile outre Manche sous Edward VI puis sous

Elizabeth, meurt à Malines en 1572. Ce curriculum vitae ne rend pas compte de

tout. Non content de l’étoffer en décrivant le manoir occupé dans l’Essex par

Clement et l’inventaire de ses biens, Thomas Merriam relève son nom dans

plusieurs documents qui suggèrent une ascendance mystérieuse :

En

1510 (postscript) John Clement participe à un pas d’armes avec Henry VIII et

des seigneurs de la plus haute noblesse, tous nés au 15e siècle. Un Joannes

Clemens anglais immatriculé à Louvain en 1489 puis en 1551 est dispensé du

serment, la seconde fois << pour une raison occulte >>. Les 62 ans

d’intervalle peuvent suggérer deux personnages, mais ce nom est rare, et la

dispense exceptionnelle. En 1534, Cromwell fait allusion à un secret concernant

John Clement et parle des ‘grands porteurs’ de ce secret. Bref, le dernier mot

n’est pas dit sur le puer meus de l’Utopie. Jack Leslau essaie avec l’auteur de

résoudre l’énigme de John Clement.

G. M.

Last Reviewed: 14 June

2000

ã 2000

Holbein Foundation. All rights reserved. Terms of Use.

Click ç “Back”

Jack LESLAU Moreana XXV, 98-99

(Dec. 1988), 17-36

The Princes in the Tower

In her clever novel The

Daughter of Time (1951) Josephine Tey presents an intriguing defense of

Richard III (1452-1485) in the matter of the death of two princes in the Tower

of London (1483?). In her book, it was not Richard III but the first Tudor king

Henry VII (1457-1509) who was responsible for the death by murder of Edward V

(b. 1470) and Richard, Duke of York (b. 1473), the sons of Edward IV

(1442-1483).

Since historic

evidence to date has not produced conclusive proof that the two boys were

killed at all, 1 leaving the case open to

renewed examination, I propose to consider a third option ; that they were not

in fact killed but were destined to live on under false names and identities as

<< notional persons >> (persons who only apparently exist). 2

A considerable amount of research and professional

assistance from various disciplines will be required in order to verify this

thesis. In the present article I can only point to a number of indications,

which seem to support the theory and my personal view. In this connexion, I

will have to introduce a negative intelligence (or evidence) evaluation

theory (NIET), which may, for its own sake and on its own merits, attract a

scholar’s attention. 3

I will summarise my initial observations and

findings under three headings :

1)

Interpretation of Thomas More’s manuscript/book (1513-1518), The History of

King Richard the Third ; 4

2)

Interpretation of Holbein’s large portrait of More’s household, in comparison

with the sketch he made in Chelsea (1526-1528) ; 5

3) Certain documentary evidence

regarding Doctor John Clement, one-time secretary of More and member of his

household, who married (in 1526?) More’s adoptive daughter Margaret Giggs. 6

Section 1

The History of King Richard

the Third

by Thomas More

(1477-1535)

A worrying feature

of the material I have to present shows that these matters were being canvassed

over a substantial period of time. 7 Interested parties raised the inherent contradictions

as a subject for discussion. It is not at all clear that the problems were read

and minuted for systematic objections. My reservations concern the official

response to the public interest – which was required to assume that all was

well. 8 This is a little troubling and we

will revert to it later.

The time-honoured

practice before tackling a work on which official reliance is placed is to ask

whether that reliance is well placed.

At the time of

writing his book (which later circulated as a manuscript and was not printed

until 1557), Thomas More was Reader at Lincoln’s Inn and Under-Sheriff of the

City of London. His public career ended as Lord Chancellor of England

(1529-1532). He was put to death for High Treason, a martyr for the unity of

the Church. He was also known as the cleverest lawyer in Europe and he indeed

acts as a patron saint of common lawyers. He was canonised in 1935.

At another level, he was the most famous intellectual of

his day in England. It might seem foolish to challenge the trustworthiness of a

book written by an author of such high intellectual and moral standing. And

yet, at the time that the princes disappeared, he was not much more than six

years old. Thomas More had no direct first-hand knowledge of the events he so

graphically and dramatically relates. He names no source. To be blunt, he was

repeating thirty-year-old street gossip.

A lawyer risks his

reputation as a serious person by allowing his name to be associated with a

book of unsubstantiated hearsay evidence. 9

The central most

serious allegation in the book – written down by a well-known and much

respected person – is that the princes had been murdered at the instigation of

their paternal uncle, Richard III.

The impression is

of a lawyer lending respectability to the story that the princes were dead. 10

However, at no time

does the author say that these things really happened. This is negative

evidence (see Note 3). Close reading shows that what the author does say is

that << Men really say >> these things happened.

My reservations are concerned with those officials responsible for

permitting a misreading of matters of fact. 11

Some points are not contradicted and are not in dispute. It is a

matter of common agreement that 191 years after the disappearance of the two

princes (1483), the skeletons of two young bodies were found by workmen in the Tower

of London (1674). Investigation reveals that the remains were of two children

(sex uncertain) aged about 13 and 10 years respectively at death. 12 An inquirer may be surprised to read that no

evidence of identity was present with the remains. What is the basis for the

assumption that the bodies were indeed those of the princes ?

It is widely agreed that reliance has been placed upon the information

contained in More’s book, commenced in 1513 (some 161 years before the

discovery of the bodies in 1674) ; i.e. the alleged murder of the two princes

at the ages of about 13 and 10 years.

The time period between the undoubted disappearance of the princes

(1483) and the date when the book was written (1513-1521), some 30 years,

merits further investigation, just as does the evidence of identity based upon

the apparent ages of the remains of two young bodies.

For the moment, my

reservations are concerned with the remains, which were removed to their final

resting place in Westminster Abbey. We may safely conclude that official

approval was sought and was given – and the public interest required to assume

all was well. 13

And yet, we must

return to the simple fact that the negative evidence was omitted. The negative

evidence – what was not there and which, reasonably, we might have expected to

find there – was disregarded.

First, the negative

evidence concerning the mother of the two princes, Elizabeth Woodville

(1437?-1492).

When a mother does

not claim that her sons are dead or missing, we may reasonably conclude that

her sons are neither dead nor missing. 14

Neither did the mother attribute responsibility for their undoubted

disappearance to her deceased brother-in-law (Richard III), nor to her living

son-in-law (Henry VII).

We may assume there was considerable risk of disclosure by the mother

should either her brother-in-law or her son-in-law attempt to abduct her two

children against her will.

This negative evidence directly contradicts the official view that the

princes were murdered and that the person responsible was either the mother’s

brother-in-law or her son-in-law. 15

My reservations concern the possibility that the princes were neither

dead not missing but had disappeared from public view with the knowledge and

consent of the mother, her brother-in-law and, later, her son-in-law.

An inquirer may be surprised to read that the possibility of a

collusive arrangement between the principals, which resulted in the

disappearance of two young children, was never tested.

It was overlooked that the disappearance of two male children from a

contested dynasty might be directly related to the silence of their mother and

the subsequent marriage of their sister (in 1486) to the leader of the

contesting dynasty.

To save her life and children’s lives and ensure the continued

well-being of her large family, the widow of Edward IV remained silent upon the

continued existence of her two sons and consented for her daughter, Elizabeth

of York (1465-1503), to marry the newly-crowned Henry VII – a collusive

arrangement with her son-in-law.

The impression is of danger to an entire country from Henry VII in the

event of any show of non-compliance ; and the activities required of a dirty

tricks department and their conscious and unconscious agents in Richard III,

Henry VII, Henry VIII and thereafter. 16

For the present, we may safely assume all was not well – far from it –

and that there is a case to answer on why the official view prevails and is

regarded as definitive.

We may also decide that there was a motive for the official reliance

placed upon a misreading of the book. Similarly, that there was a motive behind

the writing of the book. That motive becomes cogent if the princes lived on, as

conjectured.

Fear of disclosure was that motive, from first to last.

Upon the assumption that secret history is true history, I must now

introduce the new evidence of a contemporary witness, Hans Holbein the Younger

(1497/8-1543), that More’s story was a blind to lay down a smokescreen over the

continued existence of the two York princes, the uncles of Henry VIII, the brothers

of the Tudor king’s mother. 17

Section 2

The Group Portrait of Sir Thomas More and his

Family

at Nostell Priory, West Yorkshire.

The portrait is the property of the Lord St. Oswald and Trustees and

has not been out of family possession since it was painted for Margaret and

William Roper, daughter and son-in-law of Sir Thomas More. Family documents

show that it was painted by Hans Holbein the Younger, probably in the Great

Hall of the Roper family home of Well Hall, at Eltham in Kent, some time during

his second visit to England, after 1532. The painting descended to the present

owner after the marriage, in 1729, of a young Roper co-heiress, Susannah

Henshaw, to Sir Rowland Winn ; who, after payment to two brothers-in-law, in

order to gain sole ownership, brought the painting from Eltham to Nostell,

where it is on view to the public. 18

I now have to draw attention to the discreet placement by the artist of

conventional symbols in an end-on relationship with unconventional symbols (and

other unconventional elements) in the composition of this large oil-on-canvas

painting (approximately, 3,5 x 2,5 metres). But first, I have to inform the

reader of the results of my own amateur investigations into the art world.

Because there is no authority in this particular field – indeed, the

unconventional symbols are unrecorded – I tested the theory that these latter

were pictorial representations of linguistic equivalents ; and I repeated the

experiment upon several hundred similar unconventional elements contained in

seventy-three works attributed to Holbein, successfully.

I concluded that the artist had left information for posterity –

personal and political, concerning his sitters, mostly in the French language –

in a hitherto unknown secret method of communication, some sort of rebus, which

I named a covert rebus. 19

I then made a comparative study of Holbein’s original sketch of the

family group (made in 1526? and taken by him to Basel in 1528?) and observed one

major and some eighty minor changes in composition in the post-1532 portrait.

In each case the changes were relevant to the rebus. We may usefully consider

one of those changes, which concern us.

The most striking change is the artist’s inclusion of another figure

in the family group, omitted from the sketch, the man in the doorway.

For a substantial period of time this person has been conjecturally

identified as John Harris, More’s secretary. And yet he is depicted highest in

the portrait (a position conventionally reserved for the person of highest

status). The fleur-de-lys marks him (a symbol of the French kings, from

whom the Plantagenets are descended). The artist also marks him with a buckler,

a warrior’s status symbol (Oxford English Dictionary : ‘buckler’ – ‘to

deserve to carry the buckler’, ‘to take up the bucklers’ – which has early

associations with ideas of ‘worthiness’, ‘to enter the lists’).

These conventional symbols are in close relationship with

unconventional symbols – which conjecturally identify John Harris reading a

book in a back room.

The person of highest status is marked by unconventional symbols which

indicate a notional person who holds the right and title of nobility, a doctor

who is royal, husband of Margaret Clement, whose real identity is Richard, Duke

of York (depicted wearing Italian style of dress), conjecturally identified as

Dr. John Clement, who did gain his M.D. in Siena. 20

Clement is depicted with dark hair, of medium height and build. The

pose is a close reflected mirror image of the standard portrait of Richard III

and might be said to favour the cingularis image. 21 Although

a Neville descendant, like his uncle, Richard III, Clement does not favour the

tall, blond, beefy Neville men. Perhaps it should be mentioned here, without

wishing to imply that the artist’s information is prime evidence, that upon the

death of his elder brother, Edward V (who conjecturally lived under the cover

name of Sir Edward Guildford and allegedly died in July 1528), Clement became

the rightful heir to the throne of England.

We may conceivably

conclude that the story that Richard, Duke of York, was murdered (1483) is

false and that the book was indeed More’s blind to lay a smokescreen over the

continued existence of the princes and their descendants (who must be protected

from retrospective identification). 22

Although we cannot

be certain how the artist obtained his information, Holbein appears to say he

is deeply concerned that More is risking his life in such a way, that the

writing of the manuscript and its circulation may be clumsy or clever –

implying that time will tell.

However, More may

have served rightful heirs as well as legal heirs. This remains to be assessed.

The artist has sacrificed the aesthetic quality for the sake of the rebus in

some 73 pictures, something unheard of in the world of great art and, in

conclusion, I must return again to the witness, Holbein. 23

We will have to

consider carefully his paintings and whether he suffered from mythomania and if

we should believe him. Or, was it all a pack of lies ?

We must also look for a motive and explanation for the method in which

he left his information.

Clearly, he could have left his story in a diary, possibly in code,

hidden somewhere in a building, or buried in the ground for someone to find at

a later date. In this way, there would be little personal risk. But again, why

should the story be believed at any future time ? It is this central point of

risk to which I must finally draw attention.

It might seem undeniable that Holbein’s paintings were left by him,

literally ‘on the wall’, for anyone to see. They were not hidden away. There

could be no guarantee of security for his method of communication. At any

moment an enemy might have seen and understood. There was a considerable risk

of discovery, of which we may assume he was aware. In the event, the risk was

not merely confiscation of goods and chattels, but death.

Perhaps we should listen with respect, neither believing nor disbelieving,

but just remembering one brave man among many. Alternatively, we may conclude

that Holbein was a credible and independent witness at the English court, a

German observer and competent reporter of the great persons and events of the

sixteenth century – a man whose art concealed his art for posterity — which may

require some change to the recorded history of Tudor England. It is a matter

for the reader to decide what recommendations should be made and to ensure that

those recommendations should not be shuffled off until another century.

Section 3

John Clement and negative intelligence

(or ‘evidence’) evaluation theory.

A slightly worrying feature of the material I have to present shows that

we have often allowed ourselves to rely on positive evidence, such as documents

and artefacts, over a substantial period of time, without a proper system of

checks and balances. My reservations concern a system that apparently placed

reliance upon positive evidence without proper checking of the negative

evidence as, for instance, in the case of the genealogies of the royal houses

of Europe.

Few records were better kept, if any, or were more

officially authenticated. The royal genealogies are widely regarded as

unchallengeable. And yet, we must return to the simple fact that the negative

evidence was overlooked. Because of this, the risk existed that any conclusion

based upon the positive evidence was solely the product of the criteria applied

and those criteria had omitted the negative evidence which was not there ;

namely, the multiple births.

In a sample of some 50,000 royal births since the

fifth century, there is not one set of twins recorded. And yet the incidence of

twins is well known and can be predicted : at least one in one hundred births,

ten in a thousand, and some 500 in 50,000. We must not invent a new biology for

royal families. Clearly there is a case to answer concerning the apparent

non-records of the incidence of royal multiple births.

We may further conclude that positive evidence can be faked by

commission or omission -– but not negative evidence. This is our central

point.

In this section we are concerned with methods and, as in this

developing case, the method of approach to a problem is sometimes more

important – in order to obtain a correct hypothesis – than the seemingly

all-important problem itself, which may be resolved by other means.

In the case of Dr.

John Clement, we observe that he became president of the College of Physicians

without any record of family credentials, place of origin or birth. The

position was in the gift of the king.

The most careful search has revealed no official document bearing his signature.

Signatures or records of their former existence remain extant for every

president since the granting of the letters patent to the college in 1518 –

except for Dr. John Clement. Similarly, portraits or records of their former

existence remain for every president up to the present day – except Clement.

This NIET negative evidence has been confirmed by the Royal College of

Physicians and the Welcome Foundation Medical Museum, London. However, an entry in the register of the

University of Louvain, for January 1551 (already quoted in Moreana No.

97, p. 146), states (in full):

Dominus Joannes

Clemens, medecine doctor, anglus, nobilis (non juravit ex rationabili quadam et

occulta causa), sed tamen promisit se servaturm juramenta consueta.

Author’s translation :

<< The Lord John Clement, doctor of medicine,

English, of noble birth 24 (has not sworn

the oath for a reasonable hidden cause), but has nevertheless promised to keep

the customary oaths. >>

The entry is in the rector’s hand, in accordance with university

custom and rule. The rector’s bracketed explanation is unique for the period 31st

August 1485 to February 1569, when a total of 49,246 names were inscribed.

We may assume the rector was not naïve and realised that Clement was

not the name of a noble family, that he indeed knew who he was and that he

could not permit Clement to swear the oath under a false name, that perjury was

a serious matter, and the university might lose its right to the privilegium

tractus if discovered. Similarly, if this were to happen, that Clement

would no longer be protected from prosecution by the civil and ecclesiastical

authorities and that his name must be on the register in order to gain the

privilege.

The open declaration by the rector of Clement’s noble status implies

that he was aware Clement was living under an assumed name, though not for any

fraudulent purpose. This was not illegal. Clement’s profession and country of

origin are openly stated. The rector could prove that John Clement had never

sworn nor had need to swear the customary oath, that he was a special case,

for, as far back as 13th February 1489, a John Clement was first

inscribed. (See : Matricule de l’Université

de Louvain, Vol. III, ed. A. Schillings, publ. Louvain, 1958, p. 42. #

128, Johannes Clemens (non juravit)

Feb 13 1489’. 25)

In 1489 the customary age for entry to university was between sixteen

and seventeen years. On August 17 in that same year, Richard, Duke of York,

born 1473, would have reached sixteen years of age. More’s possible role in

providing a false early background for Clement, essential for a notional

person, remains to be assessed. 26

Fortunately, advances in modern technology enable

the case to be tested, reliably and conclusively. 27

If Sir Edward Guildford and Dr. John Clement were indeed brothers, it

is scientifically possible to prove (or disprove) consanguinity from a genetic

study of a suitable sample taken from each body – a small residue of tissue, or

hair. If the test proves negative, the present historical case falls to the

ground. If the test proves positive : we have grounds for further investigation